Citizen ‘journalism’ ran amok in Boston crisis

With an entire city on lockdown and the whole world watching, crowd reporting on the drama in Boston last week reached critical mass. Now, we are facing a critical mess.

Armed with iPhones, empowered by Twitter and amplified by the high-tech witch hunt known as Reddit, perhaps more self-appointed citizen “journalists” than ever broadcast whatever came to mind in an instant, unencumbered by such quaint considerations as accuracy, fairness and balance – or concern for the damage that erroneous accusations can inflict.

Fired by outrage and fear at the appalling events in Boston, the crowd blurted, bleated and brayed so much misinformation, so many false accusations and so much paranoia that they heightened the collective angst understandably triggered by the cascading horrors of the marathon bombing, the overnight police shootout and the daylong dragnet that brought a metropolis to a standstill.

If that were not bad enough, some in the mainstream media – the “Bag Men” cover at the New York Post being top of mind – joined the scrum, seemingly succumbing to the relentless pressure of Internet chatter by publishing inaccurate, unverified and defamatory information when they damn well should have known better.

As the free-for-all fulminated on the Net, a smart, sophisticated and sensitive friend from Silicon Valley said he saw no harm in the transition from classic, professionally produced journalism to the unfettered ability of all comers to publish all manner of content in the digital era. Based on what we saw last week, I couldn’t disagree more. Here's why:

To be sure, some citizens helped the authorities by providing useful photographic evidence, while others assisted the mainstream media with valuable eyewitness accounts of the serial madness in Boston.

But those contributions paled beside the many incendiary and irresponsible threads at Reddit and other sites that, to cite two of the most egregious examples, wrongfully named an innocent high school student and a missing college student as suspects in the marathon bombing. Details of each case can be found here and here.

Now, I am the last guy who will argue that professionals are more noble, more believable or more capable of producing quality journalism than unaccredited and unaffiliated individuals who take the time to properly report a development, to piece together a complex investigation or to provide well-considered commentary on matters as they see fit. The epic failure of the MSM to expose the WMD fairytale is all the evidence you need of the fallability of the professional press.

But, apart from occasional abuses by rogues (scoundrels unfortunately materialize in every profession), most professional journalists subscribe to the values of fair inquiry, accurate reporting and balanced presentation. The discipline, oversight and latency inherent in the traditional reporting and editing process helps to promote the accuracy, coherence and, therefore, the reliability of the final product.

When untrained, undisciplined or even unscrupulous people can say anything that comes to mind – as happened repeatedly during the Boston emergency – they do far more harm than good, especially in the sort of confusing and emotional situation we witnessed last week.

While citizen journalists in some cases bring welcome light to matters than need attention, the overwhelming bias in certain online venues seems to be to bring additional heat to matters that are already hot enough. Nowhere was this sort of toxic behavior more evident than at Reddit, an increasingly popular online destination for self-styled scribes when big news breaks.

In addition to vigorously spreading unfounded rumors and defaming the innocent individuals referenced above, Reddit carried a particularly obnoxious discussion on the night of the Boston shootout about what level the suspects would have attained had they been playing Grand Theft Auto, the ultra-violent videogame.

Another popular theme at Reddit was how the mainstream media had missed the story by not naming this or that phony culprit as the real bad guy. It was clear from many of the comments on the site that the crowd put more faith in the stuff they and their colleagues were posting than in what they were getting from the traditional media.

The anti-MSM meme calls to mind the findings of a national survey conducted after the 2012 presidential election by George Washington University for ORI, a strategic marketing firm. The study found that 63% of respondents believed the quality of information about the election was the same or better in the social media than in the mainstream press. Breaking down responses by age group, the researchers found that fully 57% of those between 18 and 25 had more trust in the social media than in the mainstream press.

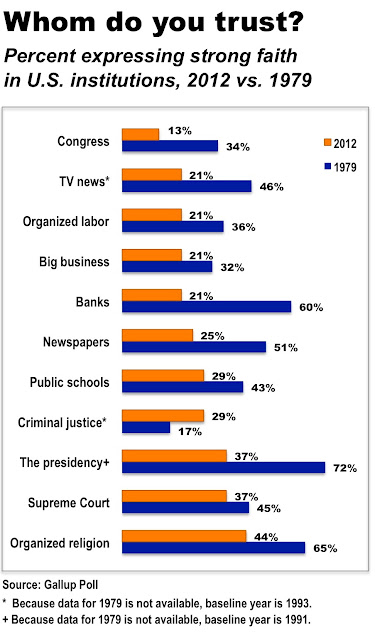

Perhaps the declining confidence in the MSM is an inevitable by-product of the widespread and growing skepticism in our age with respect to such core institutions as government, business, organized labor and religion. For a snapshot of the decline in confidence over the years, see the chart below.

While the crisis of faith in the traditional institutions of our society is frightening, the apparent transfer of trust to inherently untrustworthy sources of information is even scarier.

None of the above should be construed as a plea to muzzle the the citizen-generated media, as if such a thing were possible or advisable. There is no going back.

But we all need to take a hard look at ways that the democratization of the media enabled by digital technology can be channeled to more constructive purposes than is often the case today.

The job of mustering, coaching, vetting and encouraging quality citizen reporting could well become a major new role for professional journalists. And, who knows? It might even be a path to sustainability for the media companies that, we hope, will continue to employ them.

Why paywalls are scary

The case for paywalls would seem to be compelling: Stanch the decline in print circulation, get paid for producing valuable local content and tap into a fresh source of sorely needed revenue at a time advertising sales continue to shrink.

All good? Not necessarily. The reason to worry about paywalls is that they severely limit the prospects of developing a wider audience for newspapers at a time publishers need – more than ever – to attract readers among the digitally native generations that represent a growing proportion of the adult population.

More on that in a moment. First, the background:

It’s easy to understand why close to half of the nearly 1,400 newspapers in the United States have raced, or are racing, to charge for access to their web and/or mobile products.

In a typical digital-subscription plan, publishers start charging for access to their websites at the same time they boost the prices on print subscriptions, telling print customers that they can use the digital products for free. The higher rates, whether a customer uses digital access or not, create a revenue windfall at the same time the publisher can rightfully argue that she has provided loyal readers with substantial added value.

The revenue contribution can be significant. In a deftly crafted plan launched in the spring of 2012, the Charleston (SC) Post and Courier picked up nearly $1.6 million in combined new print and digital revenues in nine months by putting a metered paywall on its website at the same time it increased subscription fees, according to a presentation by Steve Wagenlander, the vice president of circulation of the newspaper. He spoke at the Newspaper Mega-Conference in February and his presentation is here.

Nine months into the Charleston paywall project – which was billed as a membership program and cleverly sweetened with things like free tickets to theatrical performances and the city aquarium – page views were almost as high as they were when the website was free. Gratifyingly to Wagenlander and his colleagues, only 5 of the paper’s 65,000 home-delivery customers dropped the print product in favor of a digital-only subscription. The paper also sells 25,000 single copies, for a total circulation of 90,000.

So far, so good. But here's the rub: Notwithstanding the elegant execution of the plan, the paper gained only 1,437 new digital-only customers, a sum equal to about 1.5% of its over-all circulation. The program brought in $167,612 in new digital-only revenue.

Although this performance is roughly equivalent to the industry average of the number of digital-only subscribers gained in a paywall initiative, the modest take rate is worrisome, because it means that the Post and Courier, like most other papers, is not attracting nearly as many new digital readers as it needs to.

Digital readership matters, because digital, not print, represents the future for newspapers (and most of the rest of the media, too). Unfortunately, newspapers so far have failed to attract a significant number of individuals who came of age in the digital age.

The generational disconnect is profound. Scarborough Research, a private company hired by newspapers to measure readership, reports that 68% of newspaper readers are over the age of 45. The International News Media Association, a publisher-funded research organization, reports that the average age of newspaper readers is 57. Although newspaper web visitors are slightly younger than the average age of print readers, Borrell Associates, another private researcher, reports that the newspaper web audience grows a year older every year. And we all know what eventually happens to old people.

Without younger readers to replace their steadily aging audiences, publishers run the risk of losing the relevance and scale that will attract advertisers to not only their print but also their digital products. A continued loss of revenues eventually will impair the long-term profitability and survivability of newspapers.

While paywalls for the moment seem to be doing a generally good job of extracting higher fees from loyal readers, the pay schemes that keep existing readers inside the wall are, for the most part, also keeping potential new customers out.

So, what’s a publisher do? Even as they celebrate the welcome windfall, publishers should invest their digital subscription revenues in developing new products on new platforms to attract the audiences they need – and their advertisers want.

In a word, publishers need to think mobile. And fast. The ComScore analytics service reported in its 2013 marketplace outlook that one of every three minutes of digital time now is spent with a smart phone, a tablet – or both at once.

Mobile platforms require entirely new types of interactive content and transactional services to satisfy consumers, who want to gather news quickly, locate information rapidly and share words, pictures and videos on demand.

Modern consumers are looking for a completely different experience than you will find behind most newspaper paywalls. Charging for access to something a customer doesn't want is hardly a winning strategy.

© 2013, Editor & Publisher

Newspaper ad sales skid for seventh straight year

Advertising sales, the predominant revenue stream for the newspaper industry, dropped for the seventh year in a row in 2012, falling to less than half the record $49.4 billion achieved as recently as 2005.

More on that in a moment. But first, let’s put things in perspective by comparing the meteoric rise of Google, the definitive digital media company, with the epic collapse that has cut the newspaper industry’s primary revenue stream by more than half since 2005:

As you can see in the above chart, Google came out of nowhere in the early days of the millennium to create a revolutionary way of matching specifically targeted ads to specifically targeted consumers. In less than a dozen years, this upstart start-up built a $46 billion advertising business that was twice as large last year as the combined print and digital ad sales of all of the 1,382 daily newspapers in the land.

The stunning reversal of fortune for the newspaper industry, whose consolidated revenues last year fell 6.8% to $22.3 billion in spite of a brightening economy, reflects a long-running lack of imagination and initiative that publishers are attempting to reverse by paying fresh attention to digital advertising and, in many cases, imposing new fees for access to formerly free web and mobile products.

To underscore the commitment to these new initiatives, the Newspaper Association of America, the trade group that annually reports on the industry’s financial health, argues fairly that “several” new categories of newspaper advertising are growing in spite of the long-term advertising decline.

While this certainly is true in the case of such things as digital subscriber fees – which largely did not exist a couple of years ago – and interactive marketing services, the fact is that the combined advertising and circulation revenues of the industry, which accounted for 84% of aggregate sales in 2012, totaled $32.7 billion last year vs. $60.1 billion in 2005. By any measure, the newspaper business is half the size today that is was seven years ago.

Notwithstanding a modest uptick in the broad economy, newspaper ad sales last year fell to a level not seen since 1983. The difference between then and now is that $22.3 billion in 1983 dollars would be worth $ 50.6 billion today. Revenues fell in every print category:

∷ National slumped 11.7% in 12 months to $3.3 billion. This is 58% lower than the $7.9 billion recorded at the industry’s peak in 2005.

∷ Retail slid 7.6% to a tad under $11 billion. This is 50% lower than the $22.2 billion posted in 2005.

∷ Classified stumbled 8.0% to 4.6$ billion. This is 73% lower than the $17.3 billion reported in 2005.

The only bright spot for publishers is that their digital advertising revenues gained 3.7% in 2012, generating an aggregate $3.4 billion in sales. But the digital-advertising growth at newspapers last year – as well as in the prior 10 years – pales in comparison to Google’s bodacious growth in the same period.

As illustrated in the green line in the chart above, the digital sales at newspapers and Google started out almost even in 2003 at $1.2 billion for newspapers and $1.5 billion for Google. Google’s sales doubled in 2004, handily outstripping newspapers, and then kept compounding to the point that Google’s sales were nearly 15 times greater than newspaper digital revenues in 2012.

While Google and newspapers admittedly operate in different realms of the advertising business, a comparison of their respective performance is both fair and instructive:

Newspapers (along with magazines, billboards and broadcasters) represent the traditional but inefficient “reach” model of advertising, which depends on spreading a commercial message to as large an audience as possible in hopes of connecting with qualified customers who happen at the moment to be receptive to it. Google, on the other hand, represents the highly efficient “each” model of advertising, which lets marketers put customized commercial messages next to only the results of searches containing specific keywords they have selected to target their ads. The Google system not only enables marketers to target exactly the right prospect at the right moment but also makes it remarkably easy to monitor response rates and, thus, measure an ad’s return on investment in real time.

While there is no known way for print publishers or broadcasters to provide a similar form of targeted advertising to specific individuals in their audiences, most newspapers, magazine publishers and broadcasters made the fateful mistake when the Internet came along in the mid-1990s of exporting the “reach” model of their legacy media to their products they created for the web and, subsequently, smartphones and tablets.

Instead of investing in the technology necessary to gather customer data and target advertising on the emerging digital platforms, legacy publishers and broadcasters – whether for want of insight, resources, skill or conviction – ceded the opportunity to Google and a host of other digital natives who understand that targetable customer data – not masses of unknown and undifferentiated eyeballs – is the Holy Grail of digital publishing.

In fact, the high cost and imprecision inherent in “reach” marketing is an utter turnoff for a growing number of marketers, who want to establish direct and long-lasting relationships with known customers, so as to efficiently promote purchases through well-honed individualized offers. As one example of this thinking, one major advertiser candidly confessed here to his desire to stop buying inefficient newspaper advertising as soon as possible.

The soaring growth of Google’s sales and the corresponding repudiation of print newspaper advertising objectively demonstrate a clear and growing preference on the part of marketers for “each” vs. “reach” advertising. And the velocity of the shift, as illustrated in the above chart, has been dramatic:

When the NAA first started tracking digital sales in 2003 (nearly a decade after the commercial arrival of the Internet), the aggregate print and digital ad revenues of all the nation’s newspapers were 30.7 times greater than Google’s annual sales. When aggregate newspaper ad revenues peaked in 2005, their annual sales were 7.7x greater than Google’s. As aggregate newspaper ad sales fell and Google’s revenues rose, Google and newspapers were neck-and-neck in 2009. Google overtook the combined ad sales of all the newspapers in the United States in 2010 and has been on a tear ever since, outselling publishers by 1½x in 2011 and by 2x in 2012.

Though publishers from time to time have blamed Google for taking advertising away from them, the fact is that newspapers, magazines and broadcasters never developed products to compete with Google, which now is applying the highly effective principles of keyword-targeted search advertising to banner, video and mobile advertising. In so doing, Google and its fellow digital publishers are developing ever-richer profiles of individual users to help advertisers acquire, retain and transact business with customers more efficiently than possible in the past.

As Google and other digital publishers move forward, newspapers and other legacy media companies for the most part have not committed to the bold investments in talent and technology required to deploy the contemporary and competitive digital products necessary to serve the readers and advertisers they want – and need.

If the print advertising business continues to contract in the future, publishers will have even fewer resources than they do today to transform themselves into true digital publishers. The market has voted. What are they waiting for?